Tabula Rasa

A Suburban Archaeology

Tabula Rasa is the epistemological theory that individuals are born without built-in mental content and that their knowledge comes from experience and perception…The term in Latin equates to the English ‘blank slate’ (or more accurately ‘erased slate’, which refers to writing on a slate sheet in chalk) but comes from the Roman tabula or wax tablet, used for notes, which was blanked by heating the wax and then smoothing it to give a tabula rasa.

Wikipedia

In the decade 1955 to 1964 I lived in the migrant suburb of Broadmeadows on the north west fringe of Melbourne. From 1959 to 1961 I was a student at the newly opened Campmeadows Primary School.

I attended this school in the company of two of my brothers; Jamie and Mark and with my friend Peter Van Der Veer.

In December of 2011 we revisited the suburb and the school.

The school has for several years been deregistered and is now a site of desolation and vandalism. I chose to trespass onto the site.

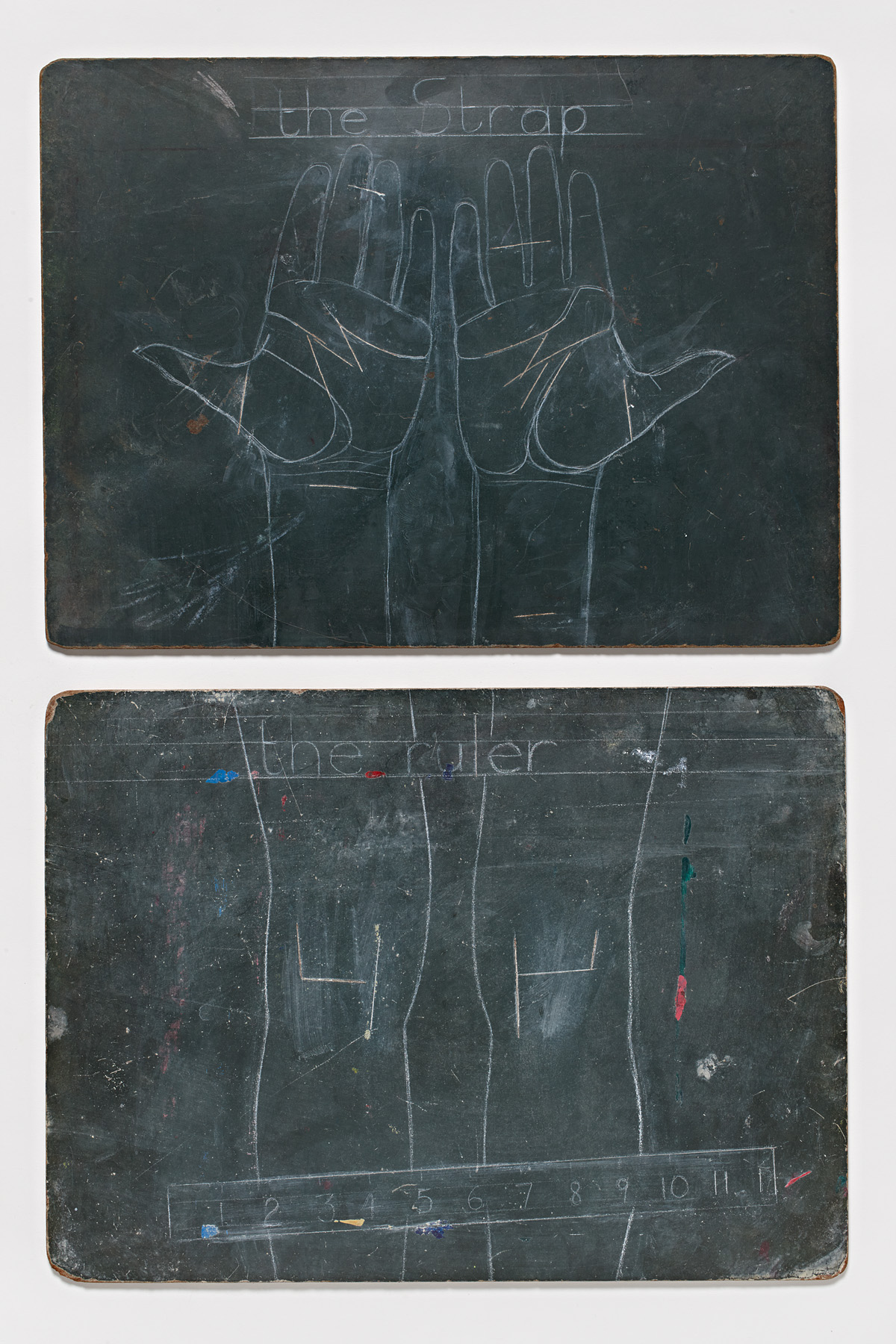

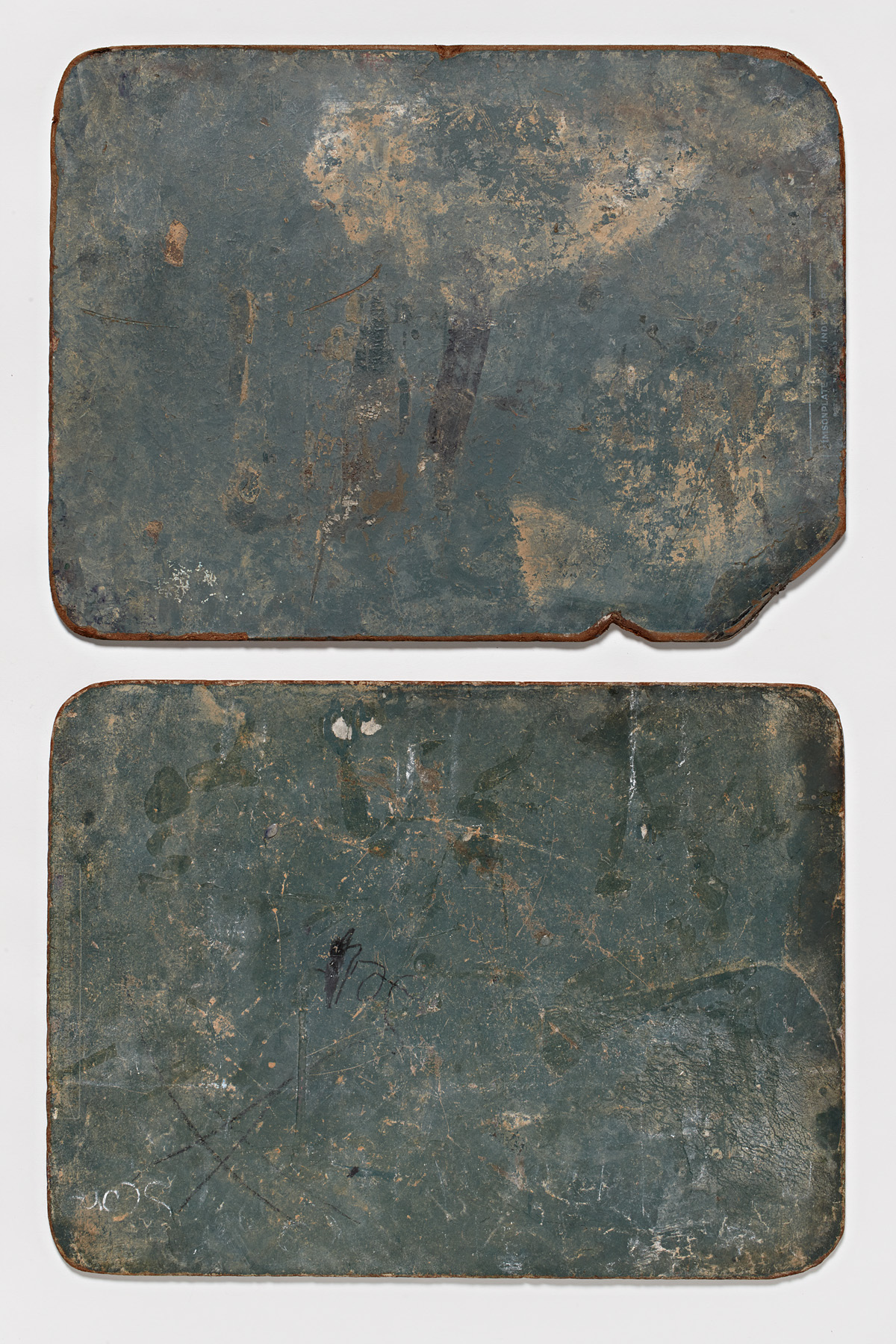

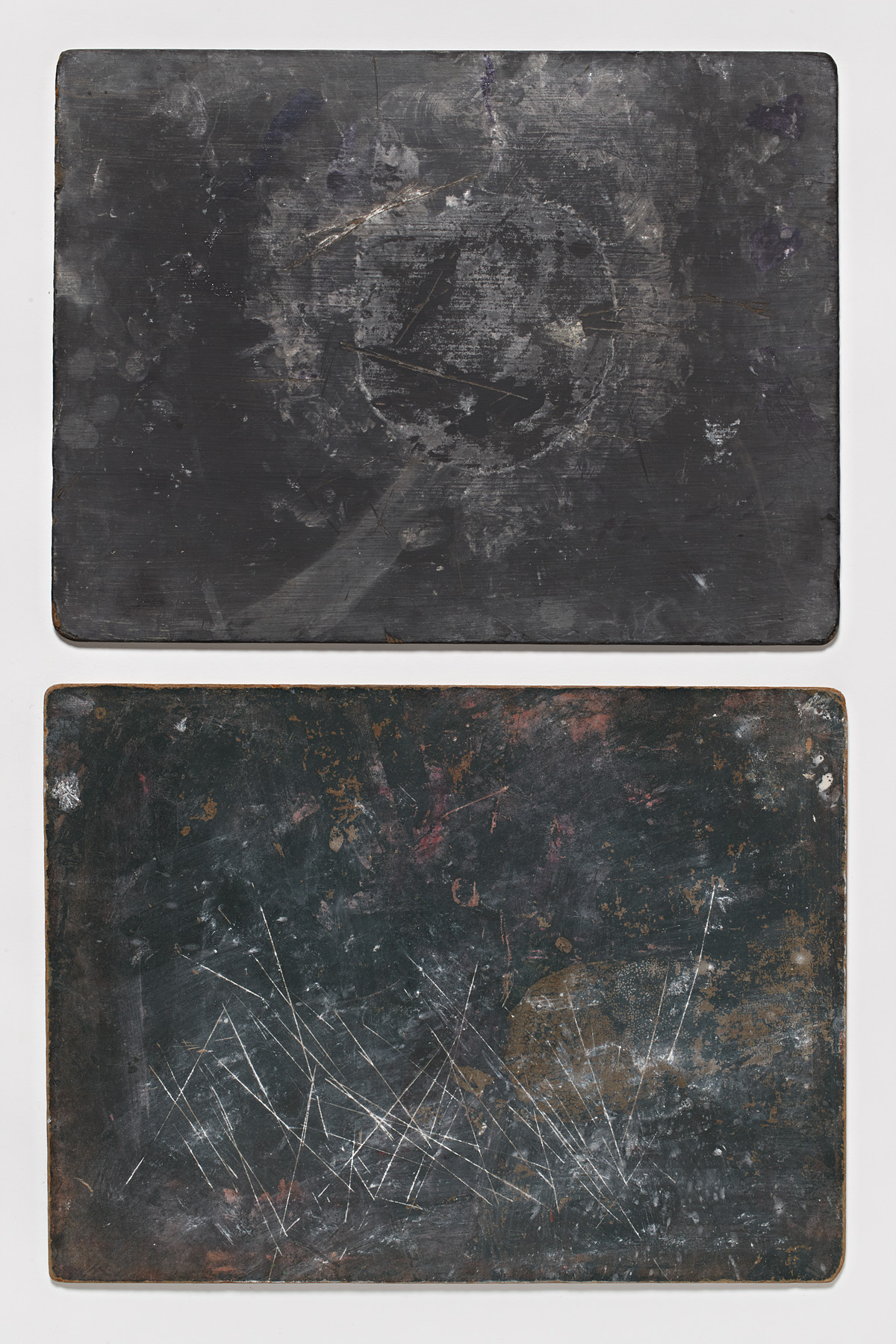

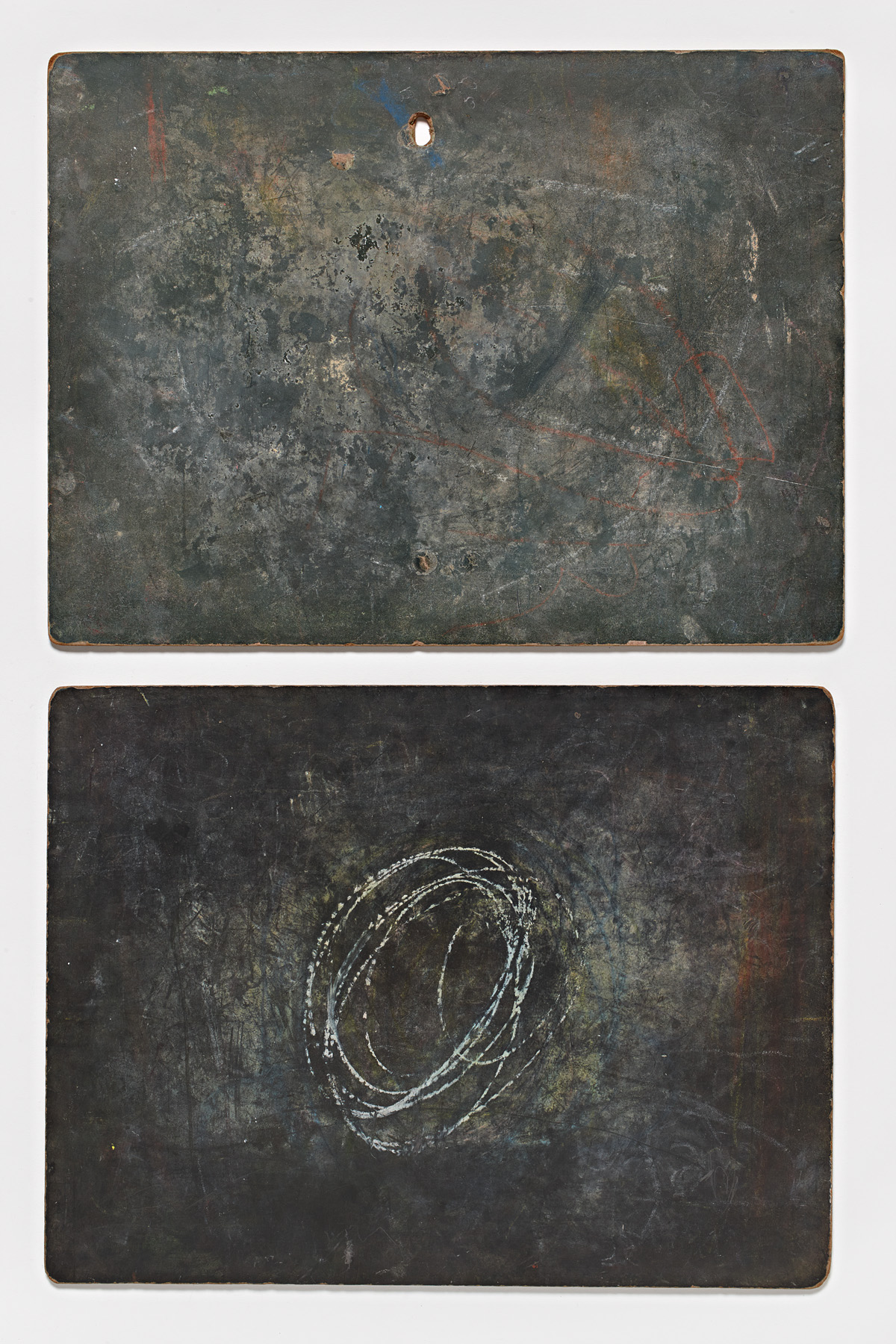

In whatever condition the school remained it would be very unlikely to find anything – other than the essential architecture – that might be a fragment of that remote era, but amid the ruin I did find something or rather I found some things: one hundred and forty five little blackboards; blackboards used then and subsequently by the junior grades; chalkboards as held in the lap of the middle kid in the front row for the annual class photograph.

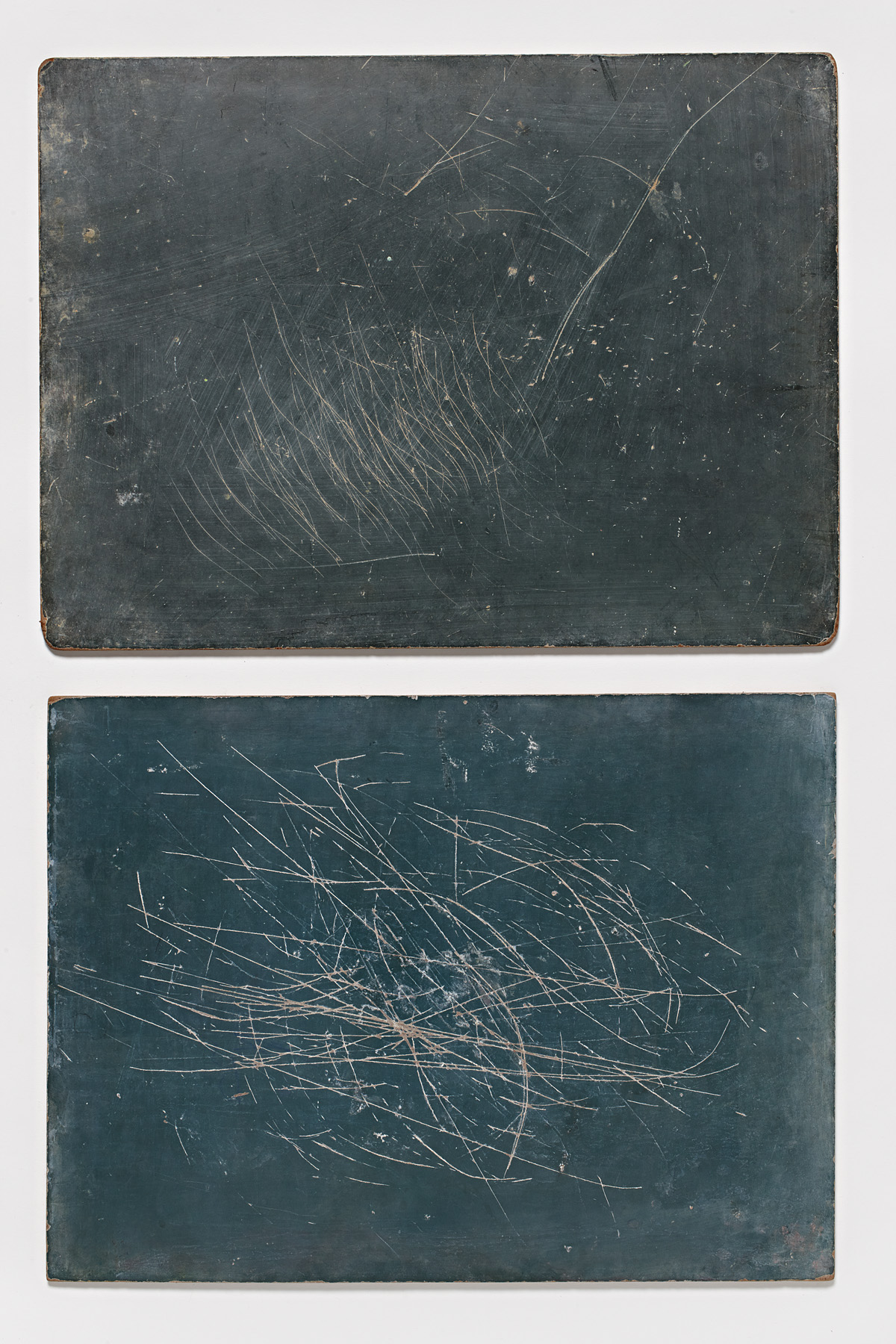

These tableaux noir - not quite black, not quite blank – are for me, a mute correspondence with the past. I imagine that they might be encoded with poignant fragments of history but it is more likely that in gathering them up – over three days – that I was merely taking possession of 145 variations of nothing.

But there is nothing that is merely nothing.

For me they isolate an aspect of beauty, in their minimalism, their obscurity, their variation and the sheer circumstance of their survival. They also seem to me to be both intimate and authentic. What is apparent to me is that the residue and fugitive markings on the majority of the boards seems familiar, similar to the lyrical calligraphies, violations and the smokey blur that I use to define and obscure my more conventional drawings.

There is, of course, an existing art language for such material and such imagery, addressed overtly by the American abstract expressionists. The artists Ad Reinhart, Mark Rothko, Cy Twombly, Joseph Beuys and Anselm Kiefer are obvious associations, and my fellow New Zealander Colin McCahon, as well.

In the early nineteen nineties I had the privilege of having my work critiqued by the artist Joe De Lutiis. Joe made reference to the sgrafitto, the sfumato, the palimpsest and the pentimenti that were rhythmically constant in my aesthetic. The observations were astute, and herein, within these objets trouvés, several generations of school children have unknowingly shared this artistry.

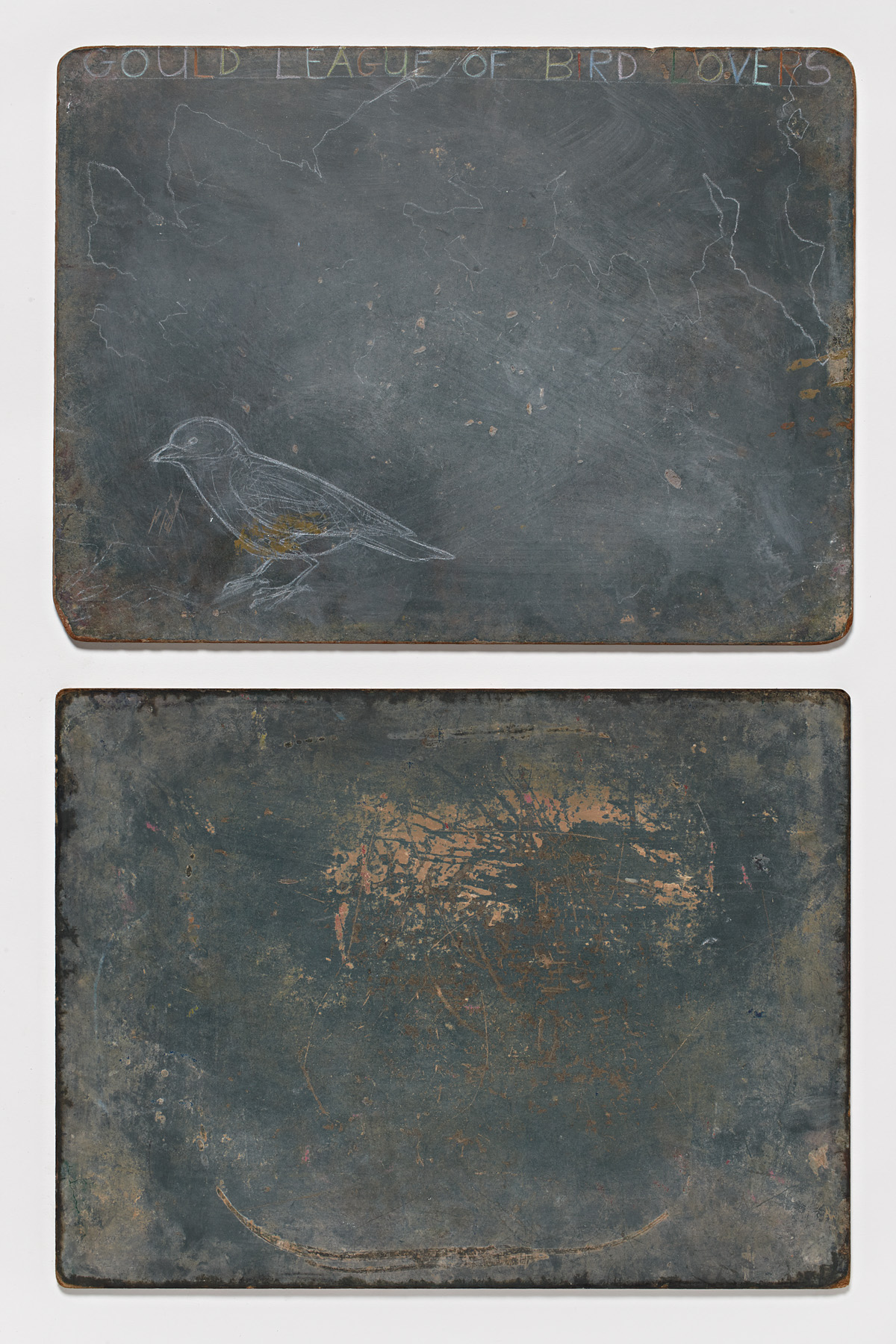

The majority of these blackboards are as they were found, each an aid to memory, meditation or imagination. A small proportion of them have been modified – with word, verse and occasionally illustration – by myself or by my companions from that time.

The G. Bradbeer of the Pythagoras Theorem is my older brother Graham and this enamel painted model of the formula was made at the nearby Glenroy Technical School, it provided for me the support for one of my first oil paintings encrusted as it is on the reverse.

For one week in 1960 I had the responsibility of being the blackboard monitor for the much-loved Miss Cattanach. I had to clean the blackboard, dust the duster (outside) and lay out the chalk on the ledge. My recent and minor interventions seem perhaps intrusive and somewhat presumptuous, but they too will fade away. More quickly if the monitor does his stuff.

My verses they are uniform

And the font is Times New Roman

No hieroglyph nor cunieform

Encrypted code nor omen

Black Star. Terra Nova

All balloons are bust

The carnival is over

The ferris wheel is rust

It could be me or thee

Just a little particle

Or it might be simply

‘the’

the finite definite article

G.Bradbeer

February 2012